Most of us intuitively know that slow moving SKUs are a problem. But just how big is this problem and why do we all have it? Why have we had it for so long; is there no resolution? In the 21-st century, with all our technology, have we not solved this problem, eradicated this curse?

WHY DO WE HAVE THEM?

We stock slow movers because customers want them, albeit sporadically. Not supplying them drives customers to our competitors. They’d search for what they want elsewhere and, finding it elsewhere, they might not come back to us! Not coming back they wouldn’t buy our fast movers! While any particular slow mover isn’t sought by very many customers, collectively they represent a respectable portion of our customers’ demand.

HOW MANY SLOW MOVERS ARE THERE?

Pareto’s Law–the 80/20 rule–suggests that 80 percent of a company’s revenue comes from just 20% of its products. If the price of a company’s products were about the same, then this law would mean that 80% of the SKUs were slow movers—contributing only 20% to revenue. In any case there are lots of them and virtually all companies with any product breadth have them.

WHY ARE THEY A PROBLEM?

Of course everyone wants fast movers, so slow movers naturally suffer merely by comparison. But it’s worse than just a comparison. Slow movers are a problem because many, maybe most, become even slower in the future. Too often slow movers are merely products on their way to dying–no demand whatever. Then we’re stuck with the stock. Dead inventory just piles up until it’s discounted, disposed of or the company is sold.

Companies are loath to deal with the financial hit of writing off excess inventory. Company after company takes the month-in and month-out hit of housing dead and dying inventory rather than dispose of it imposing the one-time asset write-off and earnings cut.

WHAT’S THE UNDERLYING PROCESS?

Many companies’ customers, perhaps most, order randomly. They place orders when they want to not on any predictable schedule. Think about when a customer might order a fender for a 2000 truck from a Ford dealer.

This randomness is particularly operational with slow movers. Orders for them typically come in quantities of one and at widely separated times. Often the most likely quantity ordered in a short period of time, say a day, is zero; but that likelihood is still less than 100%.

We represent this demand and most other demand as random and determine probabilities about it. We might be able to estimate the average demand in a specific period but we cannot know when the next demand will occur. We’re left to forecast “the rate” of this random demand and characterize individual demands probabilistically.

WHAT’S THE FORECASTING PROBLEM WITH SLOW MOVERS?

If you have an unbiased forecast–equally high or low of the actual–it will overstate the forecast 50% of the time and understate it the other 50% of the time. Overstated forecasts result in even more inventory. While this applies to fast movers too, slow movers take longer to readjust their inventory levels; many never do.

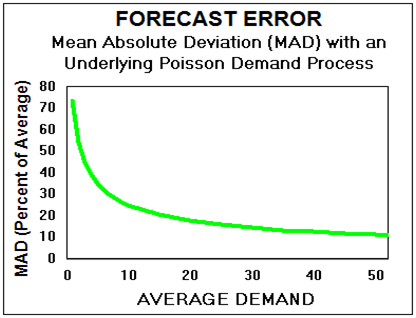

Slow movers remain notoriously hard to forecast. Some companies actually give up on forecasting slow movers. Inventory, certainly Safety Stock, depends on forecast errors–more error means more Safety Stock. The forecast error of slow movers is notoriously high. It looks like this:

For example, if the average demand of an item is 10 per month the forecast error in a month will be about 25%, even if we know the underlying demand process and its average, the 10. This error will increase if we don’t know the demand’s probability distribution or its actual average. The 25% is the best we can do! That error dramatically increases as the item becomes slower–as its average decreases.

If we want to be able to fulfill the random demand on this item we have to have it in inventory at some level. This translates to some Safety Stock or some Replenishment Quantity resulting in an On-hand inventory of this slow mover.

WHAT’S THE SOLUTION TO THIS FORECASTING DIFFICULTY?

Once a forecast is made for a stock item only two decisions remain–when to reorder and how much to reorder. The “when” decision is driven by Safety Stocks and the “how much” by Reorder Quantities. Reorder Quantities are generally influenced by reorder economics–order a week’s worth, order enough to get free freight, order a container’s worth, a Truckload, a pallet, a case and so on. So flexibility in setting Reorder Quantities to drive Fill Rates is limited because it also impacts reorder economics.

That leaves setting Safety Stocks. They are simply numbers in a file, able to be set to any value—positive, fractions, zero and even negative values. As such they have a direct impact on Fill Rates and the Capital invested in the inventory–the performance of the inventory.

Beyond forecasting well, which isn’t in the cards for slow movers, setting Safety Stocks is the most effective lever inventory planners have to control Fill and Capital. Set them right.