TEN FORECASTING FALLICIES

By Terry Harris, Managing Partner, Chicago Consulting

Much more than merely applying statistical techniques, forecasting impacts most facets of a business and should draw on more resources than it typically does. In the following we highlight ten “forecasting fallacies” we’ve run across in 20 years of watching companies struggle with forecasts and its most important follow-on activity, stocking strategy. Done well, forecasting contributes to supply chain performance, customer satisfaction and financial success. Done poorly, little else matters.

1. “Our problem is crummy forecasts”

In many companies, the forecast is blamed for far too many ills. The financial organization blames forecasts for high inventory cost and dead stock. The marketing and sales organizations blame forecasts for poor customer service and lost sales. Manufacturing blames forecasting for changing too often.

Rarely is this blanket blame justified, seldom is it helpful.

By it’s very nature a forecast is an acknowledgment that the future is not perfectly known—there’s an element of uncertainty, of randomness. It’s rare that a business operates in an environment stable enough, known enough to not need estimates–forecast.

2. Forecasting is not stocking

Forecasting and stocking are two very different activities.

Too many equate forecasting with stocking or deciding how much to have on-hand. Once a forecast is made the stocking decision, in most organizations, is automatic and invisible. The stocking decision is typically buried in the bowels of a computer system. It’s out of sight so it’s out of mind. We don’t think about the stocking decision whereas we think a lot about the forecast.

3. Having the right stocking method is more important than having the right forecasting method

Think about the variety of stocking approaches. A few are:

- A “times” worth (two weeks’ worth, for example)

- The forecast error approach

- The lead-time error approach

- More emphasis on the fast movers

- Have the items’ cost, margin or “criticality” influence the decision

- Classify items into As, Bs and Cs and apply one of these methods to each class

These are very different approaches with very different consequences in inventory performance.

Actually the stocking decision is the only real lever we have to influence inventory performance. Many think forecasting is a decision process, but it’s better characterized as a “best efforts” process—we try hard to forecast well, but it isn’t a decision. Stocking, determining how much to carry, on the other hand is a real decision. We can make that decision independent of the forecast and in any way we wish…as long as we’re willing to accept the consequences.

4. There are “perfect” forecasts

Think about flipping a coin 10 times and predicting the number of heads. The forecast of 5 is a perfect forecast. Any other number would be worse—it would be wrong more often; its error rate would be higher.

Moreover, if we knew that the number of heads came from the flip of a fair coin (as opposed to having to observe the historic pattern of actual heads and tails) we would forecast 5 no matter what that observed pattern was. Of course the number of heads from coin tosses will converge to 50%; but at first, observing the process, there would be fluctuations over and under 50% leading to forecasts different than 5 heads in 10 flips.

5. Even “perfect” forecasts are often “wrong”

Normally the number of heads in 10 flips of a coin is not 5. Actually 5 comes up only 25% of the time, so 75% of the time the forecast of 5 is wrong. No matter, 5 occurs more often than any other number. It’s still the best forecast—a “perfect” forecast.

Perhaps a more important point is that as long as the forecasting format requires that we provide one number as the forecast (virtually all forecasting systems work this way) then 5 is the only logical number.

6. Only minor improvements can be made by having the “optimal” forecasting technique

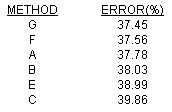

So often we’ve seen the “focus forecasting” approach touted as nirvana. In this approach items are forecast using several methods every period—every month, for example. Then the method with the lowest error is selected as the method to use.

But the difference in the best method and the second best are trivial. Typical error rates for various methods are listed below:

Despite all this “optimization” these methods are extremely close. Very little will be gained, if anything, by picking the “best” method.

Two other points on this…

- Next period, all bets are off. The methods are re-evaluated and a “new” best method is picked. That new best method has nothing to do with the previous best method. There’s nothing permanent or intrinsically best about any method. The selected method just happened to have the lowest error that month. “Best” is a fleeting concept.

- Lost in these minor details is the essence of this issue, namely, that you cannot do better than about 37% accuracy! This is the real issue and the one that the business must deal with.

7. While you can forecast future demand, you cannot “know” it.

Once you “know” the future it’s an order (or not).

If we really know what will happen, if we really know that a customer will order something, we might as well call it an order now and deal with it as such. It’s great when this happens but most businesses have an element of randomness to their order patterns. Randomness means you can’t know what will happen.

8. The most important aspects of any inventory are the service it provides (fill rate) and the capital it requires

Nothing else is more important, not even forecast accuracy.

The purpose of finished goods inventory is to be available for “random” demand. (If it’s there for known (existing) orders it’s not really inventory—it’s committed, closer to being “in-transit” or even receivables.)

We can actually achieve any performance (fill rate or availability) we want as long as we’re willing to accept the consequences. Those consequences are capital—capital now and capital in the future tied up in dead stock due to previously overstated forecasts.

So the benefit of inventory is fill rate and the cost of it is capital. Given enough capital we can achieve any fill rate we wish—just stock enough.

As explained next, however, there are lots of choices.

9. There is an optimal performance—one with the best service (fill rate) and capital

The black dot in the figure below represents a specific capital and fill rate—one that is being achieved. However, consider improving this performance by moving towards the lower right. It’s obvious that you cannot be at 100% fill with zero capital—it takes some inventory to provide a specific fill rate. As a matter of fact, you cannot even have very low capital and very high fill rate. So, as you strive to move toward the lower right, you get to a boundary, a barrier unable to be crossed. There’s an “unattainable region”. This boundary is the “optimal” performance level. It’s the best fill rate for a give capital and the best capital for a given fill rate.

10. Most inventories require too much capital and provide too little service all at the same time

Unless an inventory is performing at the peak, at some point on the curve illustrated above, it, by definition, has too much capital and too little fill rate. From any point off the curve, you can move down and to the right reaching a point on the curve and improve both fill rate and capital.

From a practical point of view, the most frequent reasons for sub-optimal performance are as follows:

- The wrong stocking methods—wrong Safety Stocks and Order Quantities, for example

- Using the same stocking approach on all items or on all items in a class (approaches that don’t account for cost, for example)

- Having the same target fill rate, say 95%, for all items regardless of their individual characteristics—lead-times, costs, velocities, and so on

- Previously over-stated forecasts that lead to larger stocking levels and, then, poor turns

- Understated forecasts that under-stock and lead to stock-outs, lost orders and lost customers

- Inaccurate lead-times—over- and under-stated leading to excess inventory and decreased fill respectively

- One-time orders that are included in an item’s history leading to exaggerated forecasts

- Data problems—inaccuracies, timing issues, level of details and so on